October 1, 2020

Let’s talk transitions.

We are struggling here with transitions at the moment.

I have always found the transition from summer to autumn has a melancholic edge. I think this is exacerbated by being in education-it always coincides with the end of a long summer holiday and the return to the daily grind.

The transition from winter to spring feels joyful and like a “breaking open”; the transition from spring to summer holds the promise of longer days, stretched out evenings and more liberty than you are used to. The transition to autumn, whilst beautiful, feels like an ending rather than a beginning.

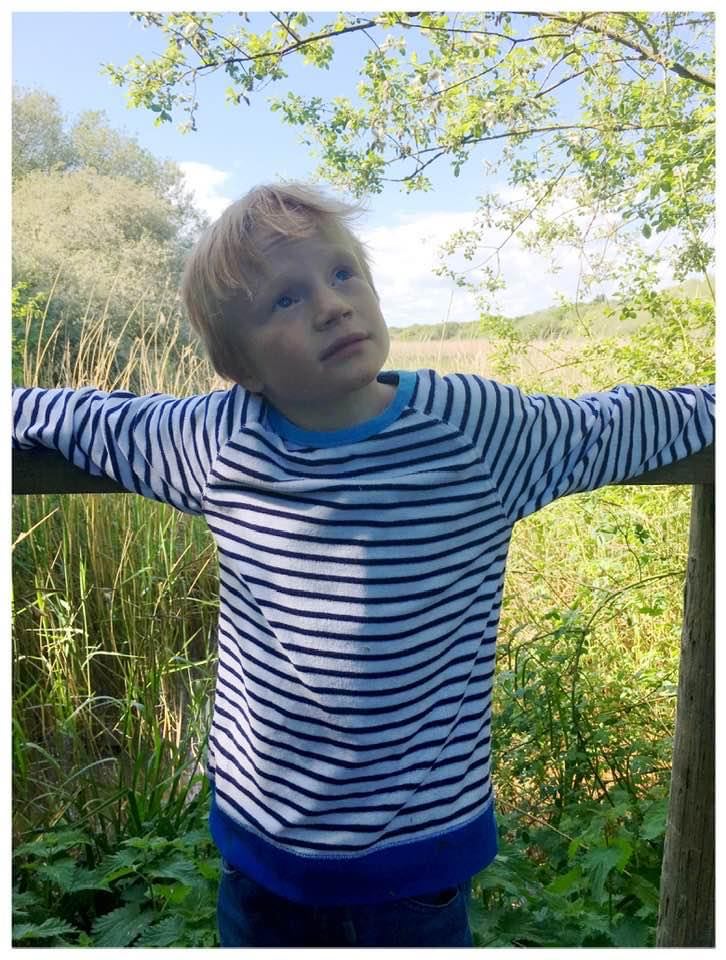

My son Finn is also struggling with transitions. The constant to-and-fro from school to home is proving to be very difficult for him to manage. School is highly structured; he has someone 24/7 to be “his person” and to help and support him. Routines are adhered to and life is predictable.

My son Finn is also struggling with transitions. The constant to-and-fro from school to home is proving to be very difficult for him to manage. School is highly structured; he has someone 24/7 to be “his person” and to help and support him. Routines are adhered to and life is predictable.

At home life is fluid. We don’t want to have a schedule on a Saturday; we don’t want a NOW and NEXT picture card to precede and punctuate every moment of our existence.

Finn awoke at the unholy hour of 3 a.m. this morning. And to cut a long story short, he kept most of us awake all night. We took it in turns and did shifts but I don’t think any of us really slept. He was noisy and very dysregulated. He was struggling with his impulse control: putting his hands in the goulash in the oven, climbing, shouting, complete and utter inability to sit still for any length of time.

By the time we got to lunch, it felt like we had been awake for several days. I was trying to get Finn to let his goulash cool down (he kept burning his mouth and lips) when I snapped,

“Finn! You’ve got to wait.”

And he replied, clear as a bell,

“Won’t cool down.”

Cue stunned silence as we all looked at each other around the table like, did you just hear that? Not just one word, but three! In a row! There was his voice! Spoken aloud.

My daughter Elsa said, “Why can’t he just do that all the time?”

I tried to explain to Elsa that inside our brains we have neurological pathways and that, for most of us, those pathways-say between thought and mouth and tongue-are clear and straight, like motorways or the Autobahn. We think something and the message is sent, fast as lightning, and delivered and processed and acted on. I speak, therefore I am.

But in Finn’s case his motorway has several hundred A roads and B roads dissecting the main thoroughfare. There are service stations and roundabouts and crossroads and roadworks and poor signage. The thought is there and the intention, but most of the time it is not delivered, or able to be acted on. And even when it does arrive, and is occasionally acted on appropriately, it is likely to have taken so long to get there that by the time he does his nervous system is likely to be stressed, frayed, and more than slightly frazzled by the crappy journey.

Today was one of the rare moments when that message was sent swift as an arrow straight down that motorway to hit the target. Sweet!

I asked Finn what his take on it was:

TALKING IS SO FUCKING HARD FOR ME. AUTISM ASKS TOO MUCH OF ME AND MY FAMILY. TAKE ME BACK TO SCHOOL. YOU ARE A FANTASTIC FAMILY AND AUTISM HAS RUINED YOUR LIFE. TAKE ME BACK TO SCHOOL AND TELL SUSAN [Finn’s social worker] TO KEEP ME THERE.

The goulash was cold by this point, and we were all in various states of tears.

Strangely it was me that didn’t have any words.

Gav does the drive to take Finn back on a Sunday. Elsa and I have got into the habit of a sunset swim in the sea on a Sunday evening, and this evening I found myself contemplating the shitty Sunday we had had whilst swimming probably for the last time this year.

Gav does the drive to take Finn back on a Sunday. Elsa and I have got into the habit of a sunset swim in the sea on a Sunday evening, and this evening I found myself contemplating the shitty Sunday we had had whilst swimming probably for the last time this year.

I lay on my back, the top of my head completely numbed by the cold water, and looked straight up at the blue sky and clouds tinged with pink at the edges, and enjoyed the sensation of being cut adrift from everyone: my children, my husband, everyone. I was the only person out there. Yet, if I lay there, and made no effort to steer myself at all. I found that the current, the tide somehow brought me into the beach, in the direction of my daughter, who was shivering inside her mustard towel, and standing at the edge of the water anxiously looking out at me.

I wish I could have found the words to explain to Finn that this is what parenthood is. Wanting to be away, wanting to be separate, but always coming back. Our internal compass pulling us towards them, wherever they are. I would have liked to explain that this is what love is-the always coming back, and that the only place I would ever really belong was with him.

~ Karren Own

Karren is a teacher in the U.K. and mum to two kids, Finn, 12, and Elsa, 9. Finn was diagnosed with autism aged 3 and autism has pretty much dominated their lives ever since. Finn is nonverbal but has learnt to communicate using a letterboard through a method known as RPM (Rapid Prompting Method). He painstakingly points to each individual letter and spells out his thoughts, feelings, ideas, preferences, hopes and dreams.

Love this!

“very dysregulated”

Interesting phrase. We all get to select how we address Autism. One common choice is to use regulation as the primary tool in our attempts to improve the quality of the lives of those in our sphere. It is not surprising to see a professional teacher deciding that regulation is a key means to solve her perception of “the problem”. Not everyone makes this choice.

Some people see the world as inherently structured, usually in a more or less linear way. Others see this perception of inherent structure as an illusion. While I commend the Saturday unstructured day (and I wonder exactly what unstructured means to this individual), this is less than 15% of the week. And then I suppose it is back to the 85+% “grind” for Finn. All of this is a series of choices.

The risk in imposing this kind of regulation this much of the time is that it regularly undermines or destroys a person’s authenticity. Once authenticity is destroyed and replaced by externally imposed regulation, the person becomes the equivalent of a potted plant, helpless, indecisive, dependent, immobilized and defeated by a massive context of artificial regulation.

There are other options. One is to support authenticity as an Autistic’s primary strength. In this learning environment consequences are more authentic in a natural way. “Unregulated” actions meet consequences that if not catastrophic are irrelevant. An Autistic child acts out in the company of strangers. What happens? Parents generally feel some shame that the child has not learned to conform to social constructs and they project on themselves that their child will face life long rejection as a result. They also often feel “failure” as a parent. Note, all this is about the parents more than about the child.

Meanwhile, the Autistic child, unless taught, does not experience such embarrassment, failure or rejection because they are “color blind” to social constructs in general. They perceive the stranger’s negative reaction to the event in their authentic way. They might feel curious, disinterest or other internal sense of the event. This is a learning opportunity about their authenticity, if the parents are strong enough to support real learning over the imposition of regulatory neuro-typical conformity.

The fear is “everyone with reject and hate my child”. Maybe, but how does this future grown up child feel about the rejection and other aspects of neuro-typical conformity? The may not give a hoot.

If authenticity is encouraged, self love, comfort, confidence and more very real impulses tend to come forward. The desire to be loyal, to be a care giver often emerge. These impulses can become, if supported, gifts of accommodation to all, including strangers. As a child becomes an adult they can be guided, not regulated, to a place where not asserting one’s authenticity becomes a gift to the narrow regulated neuro-typical world. While it is exhausting for an Autistic to subordinate their authenticity, the emotion of giving the gift of comfort to a person who cannot tolerate differences in human behavior is rewarding and often worth the extra energy it takes to pretend to conform.

I know, many here dismiss my words saying to themselves, “He is high functioning and has no idea of how my low functioning child struggles.” To this I say, high and low functioning are neuro-typical measurements. They are not real except to ableists.

Nothing About Us Without Us