When I saw the headline pass through my Facebook newsfeed, I went into the first stage of grief: That can’t be the same Alex. How strange that there are two of them. It’s an immediate defense mechanism for information that we can’t process, neurologically not unlike the Simmelweiss reflex.

When I saw the headline pass through my Facebook newsfeed, I went into the first stage of grief: That can’t be the same Alex. How strange that there are two of them. It’s an immediate defense mechanism for information that we can’t process, neurologically not unlike the Simmelweiss reflex.

Then the waves of stages 2-5 flooded me: Anger at the establishment. Bargaining. Depression. I always get stuck at “Acceptance.” The community, who showed such an outpouring of outrage and support during the crisis at Loyola, was almost silent. Each of us posted or shared carefully chosen words of shock, sympathy, heartbreak, but mostly we retreated to try to begin the impossible task of integrating and processing the end of this story that touched us all so very deeply. As hundreds of others have echoed over the months, Alex could have been my son.

My son was Alex at one point: almost non-functional, destructive, unreachable, a boy so uncontrollable that I considered residential placement when he was three. Ironically, every caseworker and social worker I spoke to came to the same regrettable conclusion: because of his diet and medical needs, there was nowhere for him to go. That was 2001, I was the newly-single parent of a vaccine-injured baby and a severely autistic toddler, and for a brief time, I prayed that we would die. I am a constitutionally optimistic, positive person, as well as not generally someone who prays, so it was huge for me to even contemplate asking, much less actively ask, an invisible deity for such a drastic outcome. I found myself in the left turn lane fervently hoping an out-of-control semi would come barreling out of nowhere just as we were halfway through the intersection.

Enter privilege. I am resilient, highly educated, and after working for 15 years on a local crisis line, no one knew where and how to reach out better than me. In a matter of weeks, I was connected with the Center for Grief Recovery in Chicago. As unusual as prayer was for me, attending the sacrament of reconciliation felt awkward. But as I unraveled the events and emotions of the past few years, I was moved to go to confession. “I actually prayed that we’d be killed,” I dared to speak aloud. I happened to be at the parish that housed the Vicar General of the Chicago Archdiocese, a wise and knowledgeable man who had somehow come across information about biomedical intervention before I had. “They’re making a lot of progress these days,” he said. “Look into it. There are a lot of treatments they didn’t used to know about.”

That exchange, the newly developed Houston enzyme products, and a few dedicated parents sharing information about their children’s recoveries on the early dial-up Internet, led to my daughter’s recovery and my son’s medical recovery. As privilege would have it, a few hours after my son took his first No Fenol enzyme, he picked up a pencil and began to draw; he is an artistic savant, a gift unlocked by appropriate medical treatment. That and the fact that medical interventions erased all his behavior issues entirely leave him with an incredibly bright future. I was moved by Alex’s story because, among other things, Alex and my son are the same age. When I saw pictures of Alex, I literally saw the ghost of what most certainly would have been, had I not been given so many unearned gifts of connection and luck along the way. Nothing I did or was caused my son to be able to medically recover. So many others aren’t given the resources or information to allow this to happen. Time and time again, we were randomly in the right place with the right person having the right conversation, leading to the next thing I knew or was able to accomplish.

The way I was raised dictates that privilege comes with a price: those who have been given much are supposed to pay it forward. It’s what those equally-exhausted autism moms whose children had already recovered did in the early days of the internet as they wrote detailed personal replies to my inquiries or spent time on long phone calls helping me interpret lab results and understand a rotation diet. I write. I’ve given talks on preventing autism, helped other moms via email, advocated online, helped people find schools. I gave an entire biomedical library to my son’s grade school. Mama Mac signed copies of the TMR book for all my son’s teachers just last month. That used to feel like paying it forward. It feels now like the community gave me the winning lottery ticket, and I gave back a few pennies.

Here are the reasons I didn’t help Alex more:

1. I am a single parent of an autistic teenager, a 12-year-old, and two young pre-adoptive foster children, one still in diapers. I wrote, called, shared and tweeted hundreds of times, but others in the community have less going on at home.

2. I work as an adjunct professor; we survive on $18,000 a year plus a little child support. I gave what I could, but others in the community have so much more.

3. I desperately wanted to take Alex into my home when I saw Dr. Wakefield’s appeal. I live a block from one of the busiest streets in Chicago, all our bedrooms are small and full, and my children’s recovery means that my home is now once again brimming with (organic) gluten, dairy, and probably some other things that would be a problem. Surely someone with a bigger and safer home would step up.

4. I’ve been reported to DCFS twice by a school counselor for Munchausen’s, “harmful substances,” (enzymes), and inadequate nutrition (the gluten and dairy free years). I’m afraid to be too visible, to get too political. If my name gets into the forefront of any given movement, they might come for me again and win this time.

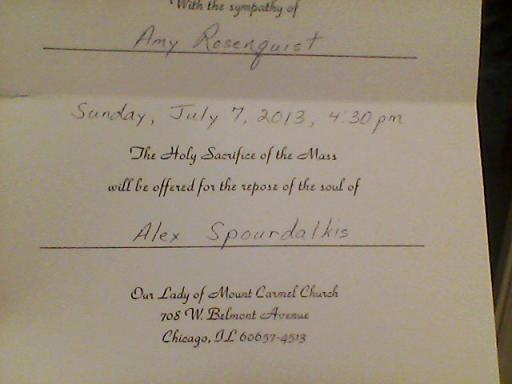

The second day after I read about Alex, I did the only thing I know to do when someone I care about dies. I went to the parish where I cantor and requested a mass. In the Catholic church, a deceased person’s name is mentioned at the end of the Prayers of the Faithful, and the congregation spends a moment in prayer. The “mass intention,” or everyone’s prayerful concentration on granting peace to that soul, is said for that person. The parish secretary apologized for the time it was taking him to get the materials together. He explained that he was just back from a three-week vacation to San Francisco, a place he was considering for retirement. It was gorgeous, he related, but the real estate, especially near the ocean, was prohibitive. I was balancing a sleeping toddler as he spoke, so I was somewhat distracted myself, but my head began to pound a little.

Alex will never reach retirement age.

Alex will never see the ocean.

The next available mass was 4:30 pm on Sunday, July 7. I was disappointed that it wasn’t sooner. I felt like I needed to sing a mass for Alex, which is my public way to mourn, a little earlier than July. Coincidentally, July 7 is also the day before my son’s 15th birthday.

Alex will never turn 15.

On the way home, the mass card tucked safely in my baby bag, my emotions finally got the better of me, and I could no longer tolerate the classical music station. I searched through the CDs for something that wouldn’t make me cry to the point that I couldn’t drive, when I came upon “A Voice for Hayden,” the song that 9-year-old Hanna Goetz wrote and sang when she saw how some people treated her autistic brother. I thought about my own 12-year-old daughter, who was moved to produce her first Youtube video to appeal for medical care for Alex. She had said: “Here is what I would want to happen, if it was my brother.” I thought about what I wished could have happened for Alex, what I would want to have happened if it had been my son. I let myself start to imagine what we, as a community, might build, if people like me could rise above whatever circumstances and fears were in the way.

This is my vision: that here in Chicago, the home of Autism One and the place where Alex lived and died, we will build the first state-of-the-art residence for children with autism, providing the best educational, behavioral, and most of all, medical treatment that the modern world has to offer. We will be a model for future autism treatment centers, because the children who come to us will fully or medically recover.

Here are the reasons the person who kicks this off shouldn’t be me:

A. I don’t even know Robert’s Rules of Order, much less how to start a foundation. But my reading comprehension is excellent; I can learn.

B. I’ve never written a grant or applied for funding in my life. But I know people who have; I can ask them, and I can learn.

C. I am no one in this community, relatively speaking. I am someone who loved Alex. I was once a hopeless mother of a severely ill autistic boy.

D. See #’s 1-4, above.

In only three years, all of my children will be in school, and I will have more hours a week to help others. In two years, I will be the same age as my father when he suddenly died. What if that’s all the time I have, as well? How will I feel if I spent my last years hoping for someone else to take the lead?

Today, my daughter is recovered.

Today, my son is alive.

I would like to suggest that as many experts, parents, and volunteers as possible come together for an open planning meeting to begin a conversation about starting the Alex Spourdalakis Foundation, which would create a residential treatment facility for severely autistic children, on Sunday July 7, 2013, from 1:00-4:00 pm in East Lakeview (Chicago). The agenda would simply be to discuss and explore forming a board. Please email me for location.

Everyone in the community is invited to attend a mass for Alex on July 7, 4:30-5:30 pm, at Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish, 708 W. Belmont Ave., Chicago. There are free parking lots to the east and west of the church. The church does not participate in a sign-in or formal greeting, so you may come and go anonymously. Non-Catholics are welcome to attend.

https://www.facebook.com/events/649612615053421/

***Please note that this is not a memorial, funeral, or official service for Alex. It is a regular weekend mass at the parish where I cantor, which will include a prayer intention for Alex during the Prayers of the Faithful.

~Amy Rosenquist

Amy: That is a wonderful idea about the memorial. I am especially hurting because my son too has the same bowel issue but we found an answer for him (see http://www.piemed.com). This is a bowel cleanout machine that keeps him well; however, he wasn’t for 2 days recently because the batteries of the machine got weak and didn’t do the complete job for the nurse and for a short time he was lying in bed, holding his belly and crying…he felt sick and really was for a short time. However, we got new batteries and completely cleaned him out a few hours later and he was happy, listening to his music which is his life and back to enjoying life. See one’s son in this shape and if you couldn’t do a thing about it…well, that is a problem I say without words to explain. But no one kills their son. I found an answer for mine. Martha

What a wonderful idea!!! I’m all the way in Texas, maybe after you all get the ball rollin’ up there some of us Texas mommas can try to follow suit down here?!! What do you say Texas MOMMAS?!?!?! 🙂

amy this is a beautiful thing..

and like you, i too would love to open up a state of the art place where you can have everything under one roof..

Amy, this is a wonderful idea, and I will try to attend on July 7th!

And, for those who don’t know… Amy is the person who planned/wrote the program for the candlelight vigil that was held for Alex in River Grove. She was also the cantor at the vigil, and provided the most beautiful, haunting musical accompaniment. The vigil probably wouldn’t have happened without her.